Physicist: To non-mathematicians this seems like a whole lot of fuss over nothing.

There’s a function called the Riemann Zeta function, denoted ““, that’s defined for complex numbers (that is, you can plug in

for example, and it’s totally fine). The Riemann hypothesis is a statement about where

is equal to zero. On its own, the locations of the zeros are pretty unimportant. However, there are a lot of theorems in number theory that are important (mostly about prime numbers) that rely on properties of

, including where it is and isn’t zero.

For example the prime number theorem, which talks about yet another greek-letter-named function, .

is defined as the number of primes less than or equal to x. So, for example,

(2, 3, and 5 are prime and less than 6).

is a lot more useful than it might seem at first blush. We unfortunately can’t give an explicit equation for

, but the Riemann hypothesis is instrumental in proving the efficacy of techniques that estimate it efficiently and (fairly) well.

Lest you think primes are unimportant; many organizations, including the NSA, snatch up every number theorist they can get, to do research on this sort of stuff. Since the late 70’s they’ve even been trying to classify mathematical proofs, or declare certain algorithms to be “munitions”, so that they can’t be written down and taken over-seas. This, by the way, is unheard of in mathematical and scientific circles. Mathematicians and computer scientists, being a cantankerous bunch (I mean, have you seen their WoW characters?), have by and large refused to play along.

Prime-number-math has really come into its own in the last several decades, what with digital stuff looking less and less like a passing fad. For example, cell phones (which are like regular telephones, but with fewer wires), essentially wouldn’t work without spread spectrum communication (to cut down on noise) and “quadratic residue sequences” (to eliminate cross-talk) which relies on some properties of primes to allow multiple digital signals to work on the same frequency band! Good times!

Answer gravy: is really weirdly defined. When it makes sense to do so, for example when s>1, it’s defined as

Where s can be any complex number. How can you raise things to complex (imaginary) powers? Good question!

Quick aside: Complex numbers are generally written as , where

is the square root of -1. Since there are two numbers in complex numbers (hence the name) you can’t have a “number line”, you need a plane, which is called the “complex plane”. The “real part” of

is the part that doesn’t have an

, and the “imaginary part” is the part that does. So if

, then Re(s)=-5 and Im(s)=3.

The summation form above “makes sense” when the real part of s is greater than 1, and as the analytic continuation of that sum when the real part is less than or equal to 1. For those values the sum can be torn apart and put back together (mathematically speaking) in a new, terrifying form that works everywhere: .

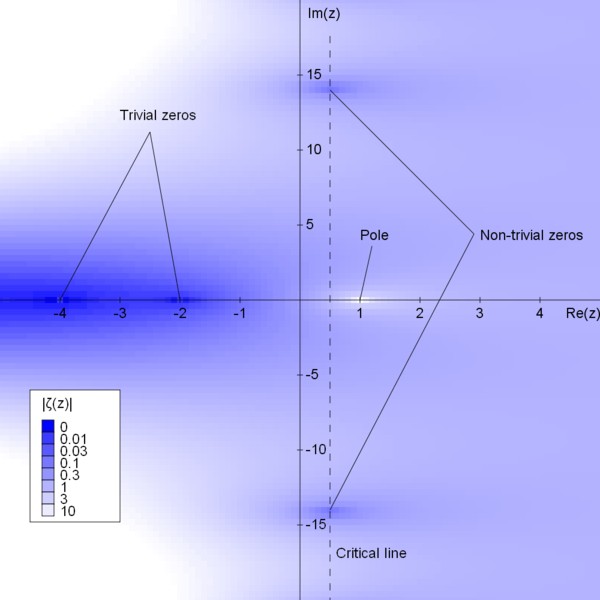

has a lot of places where it’s value is zero. Firstly at every negative even number:

. These are called the “trivial zeros” because it’s trivially easy* to prove that they’re there.

There are also other zeros called the “non-trivial zeros” that extend on, or very near, a line perpendicular to the real numbers. In fact, the statement of the Riemann hypothesis can be expressed as: “if s is a non-trivial zero of , then Re(s)=1/2″. So, the hypothesis is that all of the non-trivial zeros are exactly on the line defined by Re(s)=1/2.

The absolute value of the Riemann Zeta function for a range of values in the complex plane. Zeta explodes to infinity at s=1 and is zero when s is an even negative integer. The Riemann hypothesis is that all of the other zeros lay on the dotted line, Re(s)=1/2.

It has been proven that there an infinite number of non-trivial zeros. Of the ten trillion (give or take) found so far, all of them seem to have a real part of exactly 1/2.

Given that evidence, most mathematicians think the Riemann hypothesis is true. But trillions of confirmations do not a proof make.

One way to get some idea of why is related to prime numbers (and thus, why the Riemann hypothesis in related to primes) is to re-write

in the form of an infinite product, instead of an infinite sum:

Each term is just , where p steps through every prime (2,3,5,7,11,13,…). The product form and the summation form are the same because of the unique factorization theorem, and a little algebra.

In general, , when

. And, since

,

. When you multiply these sequences you get every possible combination of terms. For example,

will give you 1/6, 1/12, 1/8, … anything of the form 1/2n3k. Similarly, multiplying by every sequence of primes will give you every possible combination of primes and powers of primes which is just another way of saying “all integers”.

Mixing a power of “s” in there doesn’t make a difference to the derivation, but it does clutter up the notation.

*It’s not really that easy.

Pingback: Sorry, the Riemann Hypothesis Has Almost Certainly Not Been Solved | Monterey Blades

Pingback: Sorry, The Riemann Hypothesis Has Almost Certainly Not Been Solved | Gizmodo Australia

Pingback: 150-year old Math Problem: Opeyemi Enoch Has Almost Certainly Not Solved The Riemann Hypothesis claim Sceptics… | Jide-Salu.com