Physicist: A greenhouse is a little like a “light pump” that works because of the picky transparency of glass.

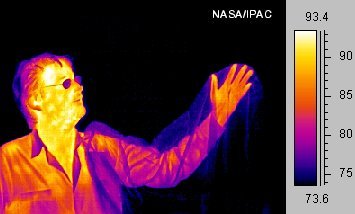

The hotter something is, the shorter the wavelength of the light it radiates (it glows bluer). The heat you feel from radiators, fires, or people is so red that it’s below the red we can see. Hence the name “infrared”.

Most of the energy in sunlight is carried by visible light, which is arguably why we can see it (no point being able to see light that isn’t around). Glass appears transparent to us because visible light passes through it, but visible light is only a tiny piece of the spectrum and no material is transparent to all light. The wavelengths of the rainbow run from about 400nm for purple to 700nm for red. Regular glass is “black” almost immediately beyond purple and not too far below red. You can’t see the ultraviolet and infrared shadows cast by glass, but you can feel them.

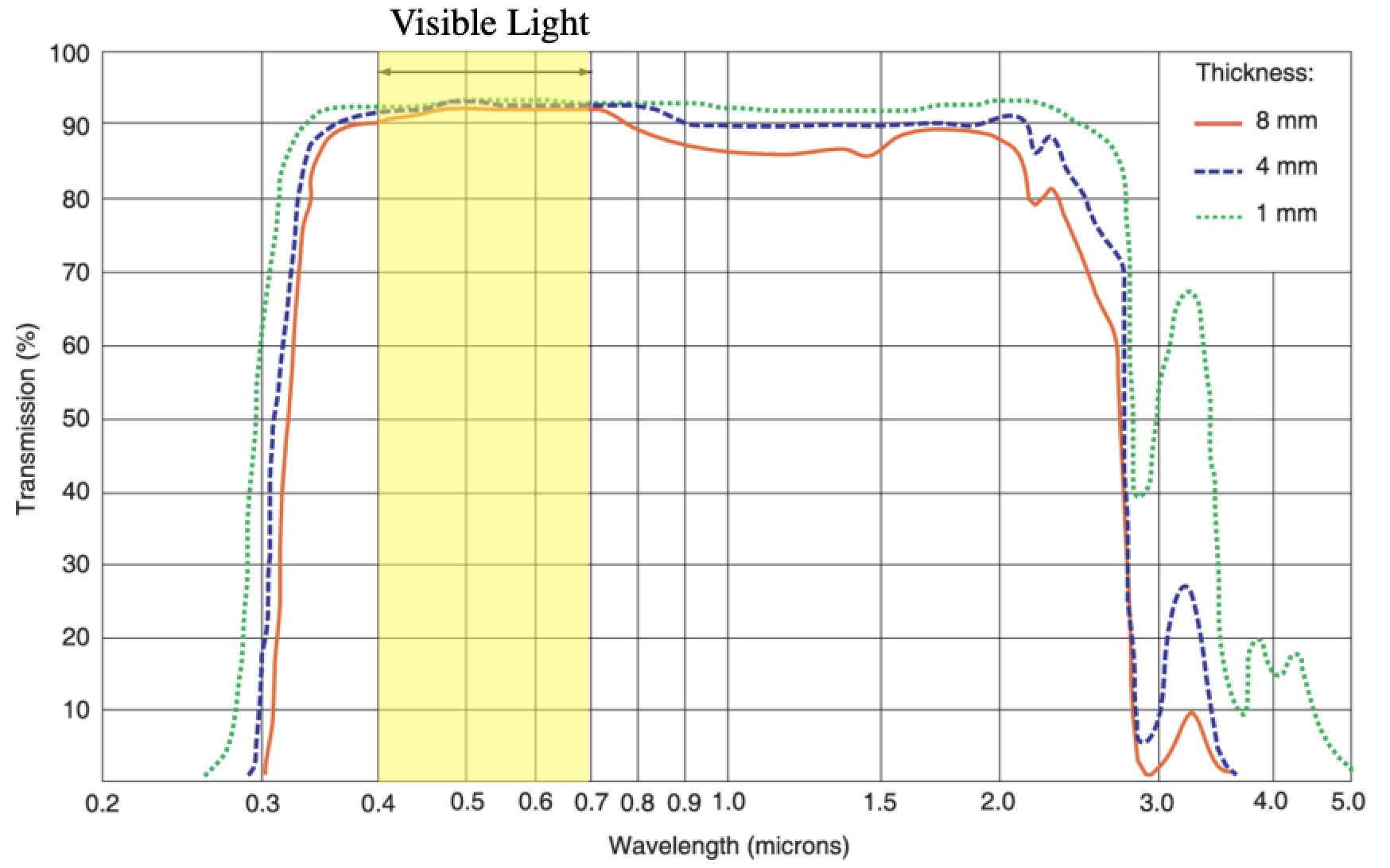

The transparency of Pyrex, which is typical of most forms of glass. The hotter something is, the shorter the wavelength of the light it radiates. The wavelength of the light that you’re radiating right now peaks at about 9.3 microns and sunlight (because the Sun is hotter) peaks at about 0.5 microns.

Get a radiator or fire that’s big enough to feel the heat on your face, then put a piece of glass in the way; you’ll still see the fire, but your face will suddenly feel cool because it’s in a shadow. On the other hand you still feel warmth from sunlight through a window, because the energy in sunlight is delivered by visible, not infrared, light.

So this is the key to why a greenhouse is also a hothouse. Visible sunlight passes through the glass, heats up whatever is inside (presumably plants), and that stuff re-radiates that energy at a longer wavelength. Instead of that light passing back through, the glass absorbs it and heats up. Warm glass conducts heat directly into the air around the greenhouse and also radiates light like any other material.

The spread of heat is completely random, so the heat in the glass “wanders” toward the outside exactly as often as it wanders toward the inside. Since the heat starts on the inside, it falls back in more often and as the glass becomes thicker. This is just a long winded way of talking about insulation; when you wear a thick coat, the heat leaving your body is more likely to “fall out” of the coat where it went in than it is to wander all the way through. And if you want to make a greenhouse that lets sunlight in, but loses effectively no heat to the outside, then you need to start with a laughably infeasible amount of glass.

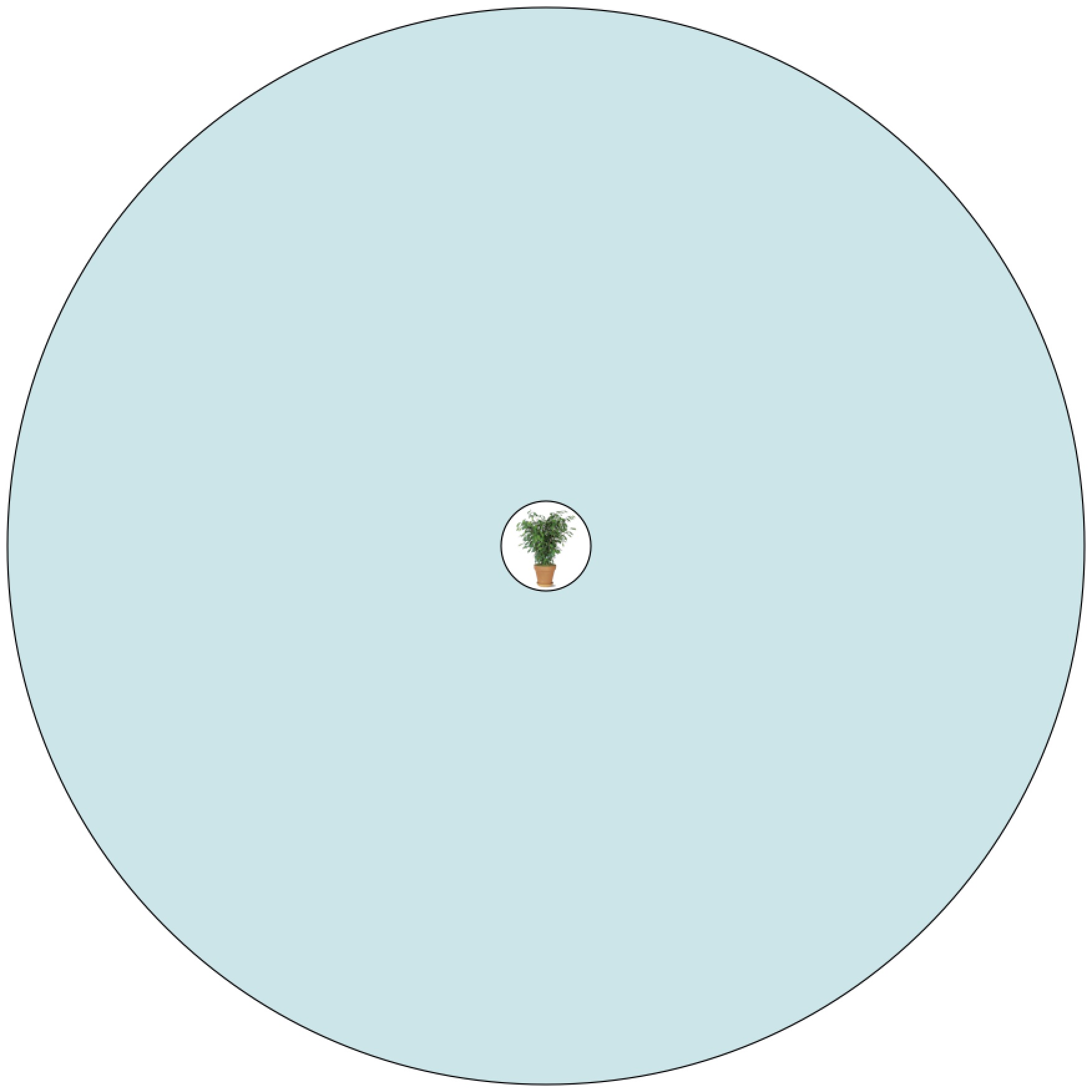

The perfect greenhouse. Sunlight passes through the glass, warming up things inside, and with enough glass that warmth is trapped.

Extreme insulation is a remarkably effective way to make things hot, as long as there’s at least a little heat coming from the inside. That’s why big compost piles are hot inside; decomposition releases a tiny amount of heat, but when it’s well-insulated by a foot or two of material, that heat (mostly) stays where it is and adds up. For a greenhouse, heat deposited by the visible light is basically being created inside and with enough glass it can be kept inside (or at least, it will escape as slowly as we’d like).

So, the theoretical limit to how hot a greenhouse can get is limited by the color of the glow of the things inside as they heat up. Eventually the spectrum of their glow will overlap the “transparency window” enough that their light will pass right through and cool off the inside just as fast as the Sun heats it up. As it happens, there’s a little math we can do. The power-per-unit-area radiated at wavelength is given by Planck’s law,

where h is Planck’s constant, k is Boltzman’s constant, c is the speed of light, and T is the temperature in Kelvin. The vast majority of Sunlight fits inside of the 0.3μm to 3μm range, so (since sunlight varies from place to place on Earth and we are talking about a massive bubble of glass instead of any kind of remotely reasonable greenhouse) we can feel comfortable estimating that all of the makes it into the greenhouse. Integrating the radiated power from the stuff inside the greenhouse over the 0.3μm to 3μm range collects all the light that can get out and tells us how fast energy escapes.

It turns out that the energy-in balances the energy-out at a little over 505K, 230°C, or 450°F. That’s famously just about hot enough for paper to spontaneously burst into flame, so if you’re going to take in the flora, don’t bring a book and don’t stay too long. The hottest possible greenhouse (on Earth anyway) would be more of a blackhouse. This may not be the optimal way to protect plants from the elements.

I didn’t really grasp your explanation. Most of us are familiar with greenhouses having temperatures far less than 450 degrees F. What exactly causes the variance in temp between these and the most extreme greenhouse you alluded to? Is it prolonged extreme external temp, or something else? Would thickness or curvature of glass also have an impact?

Would the outside temperature have some effect on how hot it can be inside? Would it make a difference if we made this in siberia or the congo rainforest?

@Rich

The extreme thickness of the glass. It needs to be so thick that it’s practically impenetrable to heat.

I suggest that the author reads the article in Wikipedia on the heating of REAL greenhouses, see especially https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Greenhouse_effect.

I quote verbatim from that Wikipedia article.

“The “greenhouse effect” of the atmosphere is named by analogy to greenhouses which become warmer in sunlight. However, a greenhouse is not primarily warmed by the “greenhouse effect”. “Greenhouse effect” is actually a misnomer since heating in the usual greenhouse is due to the reduction of convection, while the “greenhouse effect” works by preventing absorbed heat from leaving the structure through radiative transfer.

A greenhouse is built of any material that passes sunlight: usually glass or plastic. The sun warms the ground and contents inside just like the outside, and these then warm the air. Outside, the warm air near the surface rises and mixes with cooler air aloft, keeping the temperature lower than inside, where the air continues to heat up because it is confined within the greenhouse. This can be demonstrated by opening a small window near the roof of a greenhouse: the temperature will drop considerably. It was demonstrated experimentally (R. W. Wood, 1909) that a (not heated) “greenhouse” with a cover of rock salt (which is transparent to infrared) heats up an enclosure similarly to one with a glass cover. Thus greenhouses work primarily by preventing convective cooling.”

It is evident that the defining experiment was carried out as far back as 1909. Theory, however plausible, should always be verified by experiment.

“Since the heat starts on the inside, it falls back in more often and as the glass becomes .”

I think you forgot to finish your sentence there?

@SSM24

Thanks for catching that!

@Bernie

That is seriously interesting! Makes sense.

It may be the case that most of the heating in an actual greenhouse is due to blocking convection (it sounds entirely reasonable), but the back-of-the-envelope calculation here is pretty self-contained. Even if this isn’t how the bulk of the heating in a greenhouse works, I think it is how the bulk of the heating in a stadium-sized ball of very clear glass with a bubble in the middle works.

Hi guys,

How to interpret these REAL experimental results, which are described in the

link https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xX14NK8GrDY&ab_channel=PeterAxe ?

Looking forward to your answer.

Pingback: how long will black coffee last in the fridge? – Coffee Tea Room

Okay.

So, setting aside the idea of plants, is there a way to use this to capture enough thermal energy to somehow create electricity?