Mathematician: This question could mean a few different things, depending on what is meant by the word “faith.” Let’s start with the dictionary definitions.

1. Strong belief in God or in the doctrines of a religion, based on spiritual apprehension rather than proof

This has nothing to do with science.

2. Complete trust or confidence in someone or something.

You certainly don’t need complete trust or confidence to believe in the results of science. In fact, this is one of the great things about science: since results can be independently confirmed, you don’t have to trust any individual scientist much at all. In good science, researchers will check each other’s work to see if it holds up, attempting to refute what was claimed by conducting further experiments. And it would be silly to have complete trust in what science has figured out so far. When done right, the process works well at sifting out true ideas from false ones, but even then mistakes will occur which may not be caught for some time. However, when multiple experiments by competent, independent teams confirm a result, we can say that it is very likely to be true (or at least, represent an accurate model of reality).

Sometimes, when people say “science requires faith”, what they are trying to get at is the idea that scientists have to rely on assumptions that they can’t prove. For instance, scientists have to assume that induction works (e.g. that you can generalize about the future laws of the universe by looking at the past laws). If tomorrow the laws of physics were suddenly different than they ever were before, science would be in pretty deep water. The thing is though that all methods for drawing conclusions about the world rely on some hidden assumptions, so saying this is true for science isn’t saying much. In fact, the deep rooted assumptions that science relies on are pretty modest.

When people are able to build working satellites, lasers, bridges and computers using certain methods for acquiring and applying knowledge, it’s strong evidence that the assumptions made by the methods can’t be that unsound.

Physicist: No. Exactly no.

In fact having an unshakable belief, even in a particular scientific idea, is detrimental (scientifically speaking).

At the risk of making science sound like the sport of jerks; a good scientist is someone who trusts nothing and no one and is willing to drop their deepest held beliefs as though they were a bucket full of red-hot cobras. “Science” is nothing more than looking carefully at the world, while trying not to delude or trick ourselves too much, and seeing what’s what. As a result you find that, unlike conclusions based on faith (which I’m not knocking, good on you if you have them) conclusions based on careful consideration of the world tend to show up independently and frequently.

So while the Conquistadors and Aztecs may have had some subtle differences of opinion about feathered gods and whatnot (who can remember), they already agreed on a lot of stuff involving seasons, water pumps, and astronomy, among other things (though not astrology, oddly enough).

But it’s easy to lose track of all that. When Sagan says “We are made of star stuff“, as both inspiring and accurate as that is, it still sounds a bit like some kind of ancient creation myth (it also doesn’t help that Sagan was rocking the ’70s vibe). When you get right down to it, the universe is really weird.

So the claims/findings made by science seem about as crazy as the claims made by everybody else‘s religions (not yours or mine of course): time slows down when you move fast, all matter and energy is made of waves, your mind controls reality*, there are an infinite number of parallel universes**, every living thing is descended from goo or something, the universe is billions of years old, our bodies are made of trillions of semi-independent living things, most of the stuff in the universe is invisible and ghostly, the Earth was once ruled by gigantic monsters that were destroyed by a rock from the sky, the world is really a sphere that’s whipping through an infinite void at hundreds of miles per second while in the company of other spheres some of which are so much larger that Bambi v. Godzilla seems kinda fair, and on and on.

(*Not even remotely true, but you still hear it attributed to “science”. **This is so misquoted and misunderstood that it’s safer to say that it’s false, but it is something science people say.)

It’s easy to see why science seems like just some wacky new belief system that you have to have faith in to believe. The difference is, if you don’t believe it (and you’re properly motivated), then you can go out and test it. To be fair, most people do take science on faith. It’s much harder to test things yourself, than it is to trust that the kind of people who can figure out how to fly around in space and build fancy computers have things pretty well sorted out. But keep in mind; the option is there.

By the way, here are some fairly interesting, slightly dangerous, things you can test yourself.

Scientists, being a lot like people, have a hard time believing the same weird stuff that bothers everyone else. I mean, seriously, gigantic monsters? Something becomes “scientific knowledge” after many people have tried their damnedest to prove it wrong and ended up verifying it instead.

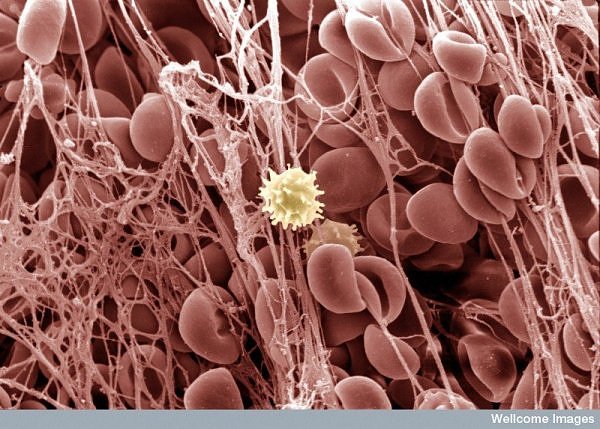

For example, nobody really believed that time slowed down for things that move fast, so (and this was just one of many tests) a couple of dudes put some ridiculously accurate clocks on some airplanes and flew them around to check. And why would anybody think that we’re made of lots of tiny living things? If you don’t believe it (and why would you?), get a microscope and a little skin or blood and take a look. It’s hella gross.

Even Schrödinger (of equation, cat, and trance-techno fame) didn’t believe several of the clearly impossible implications of his own equation (like quantum tunneling) until they were experimentally verified.

Some of the more obscure stuff takes a bit more work (money), but at the end of the day when something is “scientific fact” it’s been verified many, many, many times, until the strange and inescapable facts about the universe are forcibly inflicted upon the pitiable scientists who study it. Science isn’t about making bizarre pronouncements and then having everybody nod sagely and agree on faith. It’s about making bizarre pronouncements and then throwing it to your colleagues to fall upon and mercilessly tear apart, like ivory tower hyenas. However, physical reality always has the last word. If an idea doesn’t stand up to observation and experiment, it’s gone.

Faith is about knowing and certainty, while science is about learning and doubt. You don’t need either for the other.

31 Responses to Q: Do you need faith to believe in science?