Physicist: Colors exist in very much the same way that art and love exist. They can be perceived, and other people will generally understand you if you talk about them, but they don’t really exist in an “out in the world” kind of way. Although you can make up objective definitions that make things like “green”, “art”, and “love” more real, the definitions are pretty ad-hoc. Respectively: “green” is light with a wavelength between 520 and 570 nm, “art” is portraits of Elvis on black velvet, and “love” is the smell of napalm in the morning.

But these kinds of definitions merely correspond to the experience of those things, as opposed to actually being those things. There is certainly a set of wavelengths of light that most people in the world would agree is “red” (rojo, rubrum, rauður, 紅色, أحمر, ruĝa, …). However, that doesn’t mean that the light itself is red, it just means that a Human brain equipped with Human eyes will label it as red.

You can create an objective definition for green (right), but that’s not really what you mean by “green” (left).

Color is fascinating because, unlike love, its subjectiveness can be easily studied. We can say, without reservation, that a colorblind person sees colors differently than a colorseeing person.

Different people and animals see color very differently. The right side is more or less the way most other mammals, as well as red/green colorblind people, see the world.

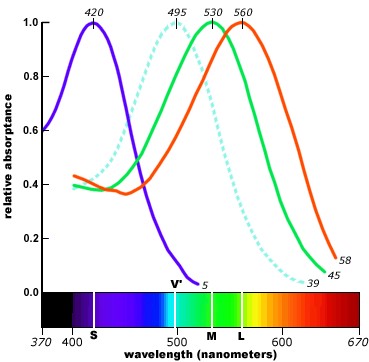

When a photon (light particle) strikes the back of the eye, whether or not it’s detected depends on what kind of cell it hits and on the wavelength of the light. We have three kinds of cells, which is pretty good for a mammal, each of which has a different probability of detecting light at various wavelengths. One of the consequences of this is that we don’t perceive a “true” spectrum. Instead, our brains have three values to work with, and they create what we think of as color from those.

The three cones cells, and their sensitivity to light of different wavelengths. The dotted line corresponds to the sensitivity of rod cells, which are mostly used for low-light vision.

However, some animals have different kinds of cone cells that allow them to see colors differently, or see wavelengths of light that we don’t see at all. For example, many insects and birds can see into the near-ultraviolet which is the color we don’t see just beyond purple. Many birds have ultraviolet plumage, because why not, and many flowering plants use ultraviolet coloration to stand out and direct insects to their pollen.

Left: what people see. Middle: a false-color simulation of what insects may see. Right: a black and white ultraviolet only image

In the deep ocean most animals are blind, or have a very limited range of color sensitivity (it’s as dark as a witch’s something-or-other; what is there to see?). But some species, like the Black Dragonfish, have taken advantage of that by generating red beams of light that they can see, but that their prey can’t.

The Black Dragonfish cleverly projects red light from those white thingies behind its eyes, which is invisible to its prey.

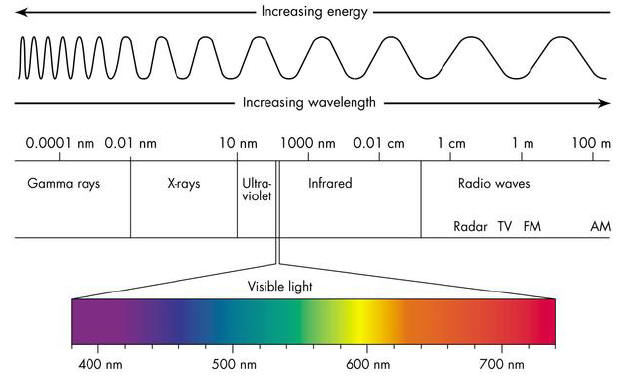

It may seem strange that some creatures are just “missing” big chucks of the light spectrum, but keep in mind; that’s all of us (people and critters alike). The visible spectrum (so called, because we can see it), is the brightest part of the Sun’s spectrum. Since it’s what’s around, life on Earth has evolved to see it (many times!). But, there is a lot more spectrum out there that no living thing comes close to seeing.

Point is, light comes in a lot of different wavelengths, but which wavelengths correspond to which color, or which can even be seen, depends entirely on the eyes of the creature doing the looking, and not really on any property of the light itself. There isn’t any objective “real” color in the world. The coloring of the rainbow is nothing more than a shared (reliable, consistent, and kick-ass) illusion.

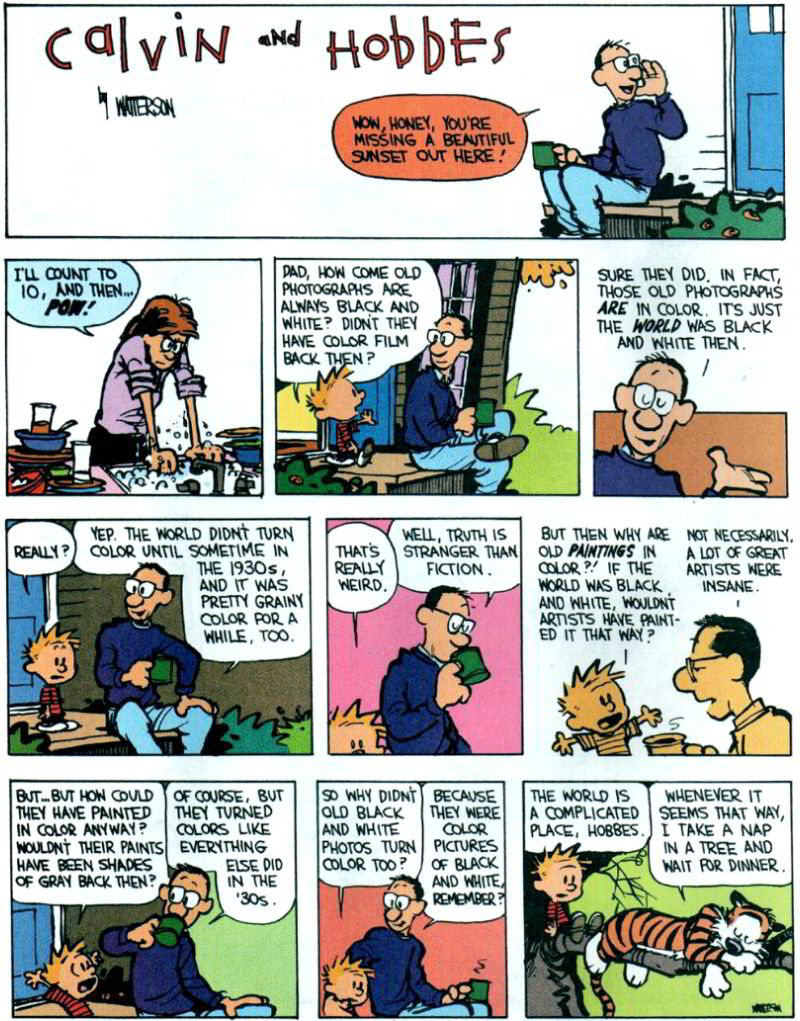

The lack of objective colorness is a real pain for the science of photography. Making a substance that becomes (what we call) yellow when it’s exposed to (what we call) yellow light is exactly as difficult as creating a substance that turns magenta when exposed to yellow light. In a nut-shell, that’s why it took so long for color photography to come along, although there are other theories:

So, it’s difficult to design film that reacts to light in such a way that we see the colors on the film as “accurate.” But, in the same sense that yellow may as well be magenta (for all that the film cares), infra-red may as well be red! You can (were you so motivated) buy infrared sensitive film that photographs light below what we can see, but above what most people call “heat” (the light radiated by warm, but not glowing-hot, objects).

A picture using film that’s sensitive to near-infrared light. This is not a picture of heat (that would use far-infrared), living plants just happen to be infrared-colored.

In fact, most “science pictures” you see: anything with stars, galaxies, individual cells, etc. are “false-color images”. That is, the cameras detect a form of light that we can’t see (e.g., radiowaves), and then “translate” them into a form we can see. Which is fine. If they didn’t, then radio astronomy would be stunningly pointless.

Infrared photo by Richard Mosse.

Pingback: Dr Jason Fox