Physicist: Singularities are just artifacts that fall out of math. They show up a lot in theory, and (probably) never in nature. The “singularities” most people have heard of are black hole singularities.

In practice, when you’re calculating something in physics and you find a singularity in your calculation (this happens all the time), which usually looks like “1/x”, then that means that there’s a mistake somewhere, or you’re looking at something that never happens, or there are physical laws or effects that haven’t been taken into account.

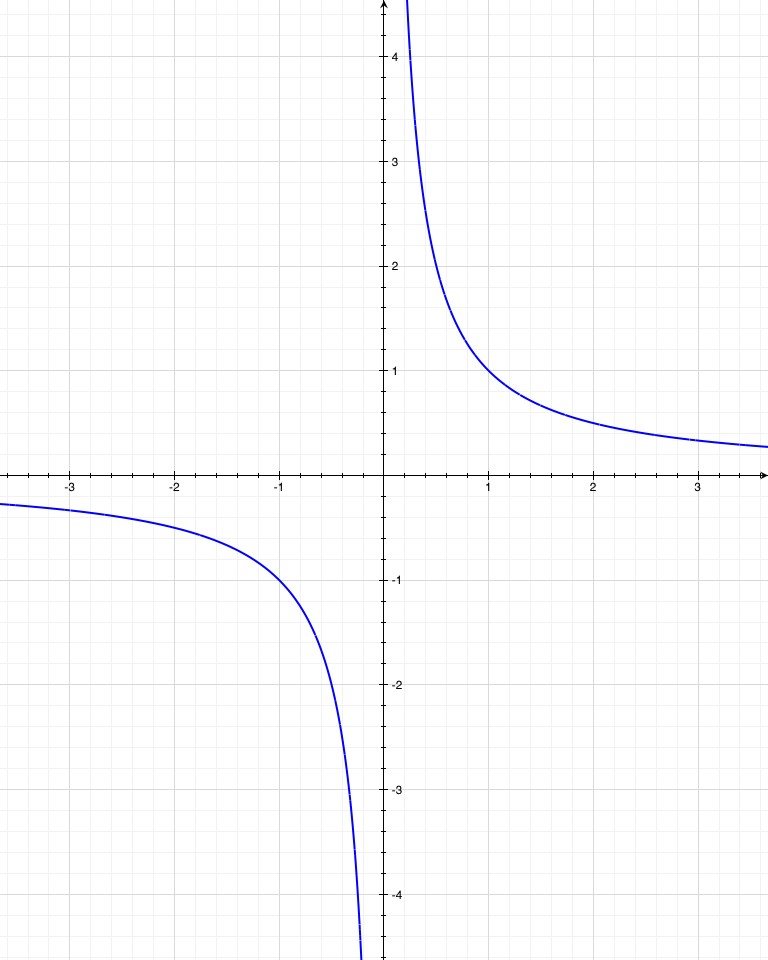

The simplest mathematical singularity: 1/x. The closer you get to zero, the more 1/x blows up, and at x=0 the function is undefined.

For example, when you drain water from a tub or sink the water will spiral into the drain. A back of the envelope calculation (based on known principles) shows that the speed, s, that the water is moving is , where r is the distance to the center of the spin, and c is a constant that has to do with how fast the water was turning before you pulled the plug. Notice that this equation implies that as water gets closer and closer to the drain, it will move faster and faster, and that right over the drain it will be moving infinitely fast. So how does the universe find an out? This will look familiar:

One of the slick tricks that water uses to avoid spinning infinitely fast at the center of a vortex: not being there.

Even when you’re deep underwater there are outs; turbulence, cavitation, that sort of thing.

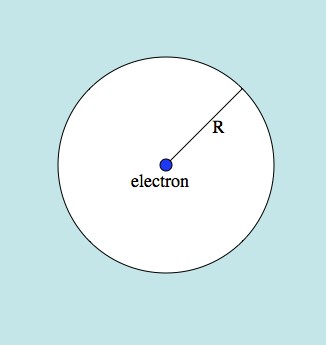

A slightly more obscure example is the energy of a charged particle’s electric field. If you have an electron just sitting around, the energy, E, of its field outside of a distance, R, from the electron is .

The electric field being considered is the light blue area. The most intense part of the field is close to the electron, so as R gets smaller and smaller, the total energy gets bigger and bigger.

Most of that is just equation porn. The important bit is the ““. Once again there’s a mathematical singularity in an equation describing a physical thing. But, once again, the universe (being sneaky) finds a way out. This is a hair less intuitive than the whirlpool thing, but in quantum mechanics an electron is described as being “smeared out” (in an uncertainty principle kind of way). It doesn’t exist in any one place, so the idea of getting infinitely close doesn’t really make sense.

The whirlpool thing and the electron thing (and hundreds of other examples) are examples of singularities that show up in the math, but can be explained away through experiment and observation, and shown to not be singularities in the physical world.

In general relativity, the shape of spacetime near a spherical mass is given by:

Now, unless you’re already a physicist, none of that should make any sense (there are reasons why it took Einstein 11 years to publish general relativity). But notice that, as ever, there’s a singularity at r=0. This is the vaunted “Singularity” inside of black holes that we hear so much about.

Something like a star or a planet doesn’t have a singularity, because this equation becomes invalid at their surface (this equation is about the empty space around a mass). But, for a black hole the gravity is so intense, and spacetime is messed up so much that it looks as though there’s nothing to stop matter from becoming infinitely dense. However, unlike the singularity over the drain in your sink, the singularity in a black hole can’t be observed. Which is frustrating.

I suspect that what we call the singularity in black holes either doesn’t exist (there is some law/effect we don’t know about) or, if cosmic censorship is true, the nature of that singularity both doesn’t matter and can’t be known, since it can never interact with the rest of the universe. There are some theories (guesses) that would fix the whole “black hole singularity problem” (like spacetime can only get so stretched, or some form of “quantum fuzziness”), but in all likelihood this is just one of those questions that may never be completely resolved.

The whirlpool photo is from here.

Pingback: Q: Why does gravity pull things toward the center of mass? What’s so special about the center of mass? | Ask a Mathematician / Ask a Physicist

Pingback: Zeno, Paradox, and Contemporary Confusion

Pingback: Laurent and the Dirac Problem – fauxmat