Physicist: This is a question that comes up a lot when you’re first studying linear algebra. The determinant has a lot of tremendously useful properties, but it’s a weird operation. You start with a matrix, take one number from every column and multiply them together, then do that in every possible combination, and half of the time you subtract, and there doesn’t seem to be any rhyme or reason why. This particular math post will be a little math heavy.

If you have a matrix, , then the determinant is

, where

is a rearrangement of the numbers 1 through n, and

is the “signature” or “parity” of that arrangement. The signature is (-1)k, where k is the number of times that pairs of numbers in

have to be switched to get to

.

For example, if , then

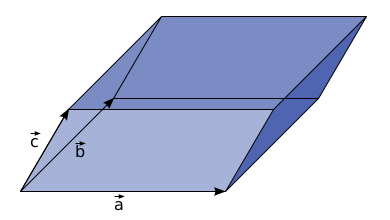

Turns out (and this is the answer to the question) that the determinant of a matrix can be thought of as the volume of the parallelepiped created by the vectors that are columns of that matrix. In the last example, these vectors are ,

, and

.

Say the volume of the parallelepiped created by is given by

. Here come some properties:

1) , if any pair of the vectors are the same, because that corresponds to the parallelepiped being flat.

2) , which is just a fancy math way of saying that doubling the length of any of the sides doubles the volume. This also means that the determinant is linear (in each column).

3) , which means “linear”. This works the same for all of the vectors in

.

Check this out! By using these properties we can see that switching two vectors in the determinant swaps the sign.

4) , so switching two of the vectors flips the sign. This is true for any pair of vectors in D. Another way to think about this property is to say that when you exchange two directions you turn the parallelepiped inside-out.

Finally, if ,

, …

, then

5) , because a 1 by 1 by 1 by … box has a volume of 1.

Also notice that, for example,

Finally, with all of that math in place,

Doing the same thing to the second part of D,

The same thing can be done to all of the vectors in D. But rather than writing n different summations we can write, , where every term in

runs from 1 to n.

When the that are left in D are the same, then D=0. This means that the only non-zero terms left in the summation are rearrangements, where the elements of

are each a number from 1 to n, with no repeats.

All but one of the will be in a weird order. Switching the order in D can flip sign, and this sign is given by the signature,

. So,

, where

, where k is the number of times that the e’s have to be switched to get to

.

So,

Which is exactly the definition of the determinant! The other uses for the determinant, from finding eigenvectors and eigenvalues, to determining if a set of vectors are linearly independent or not, to handling the coordinates in complicated integrals, all come from defining the determinant as the volume of the parallelepiped created from the columns of the matrix. It’s just not always exactly obvious how.

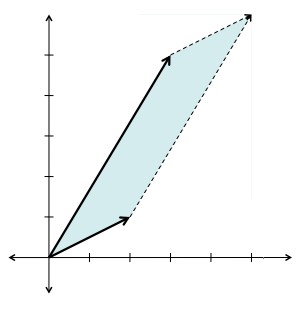

For example: The determinant of the matrix is the same as the area of this parallelogram, by definition.

Using the tricks defined in the post:

Or, using the usual determinant-finding-technique, .

Pingback: Carnival of Mathematics #99 « Wild About Math!

Pingback: TWSB: We’re In the Matrix | Eigenblogger

Pingback: TWSB: We’re In the Matrix | Eigenblogger