The original question was: Here’s my current dilemma: how does one rigorously prove the invariance of the space-time interval? In Taylor & Wheeler’s Spacetime Physics, they basically show one very good example of the invariance, then they instruct the reader to take it as gospel (In case you don’t have their book completely memorized, go here and read pg 22-25). They then use the interval’s invariance to develop the Lorentz transformation. I did a smidge of research online, but I can’t find an argument that doesn’t use the LT to prove the interval’s invariance. Is it possible to establish the LT without the invariance of the interval?

Physicist: It’s worth noting real quick that this post is aimed at people who have recently taken intro relativity. That said, if you’re hip with pre-calc, then you’re ready for the basics of special relativity (like this post).

The regular distance, D, between two things located at the points (X1, Y1, Z1) and (X2, Y2, Z2) is found using D2 = (X1-X2)2 + (Y1-Y2)2 + (Z1-Z2)2. This is basically just the Pythagorean theorem.

But when relativity came along it became important include time, T, along with the the three spacial coordinates, X, Y, and Z. An “event” is something that happens at a particular place and time. So, event 1 happens at (X1, Y1, Z1, T1) and event 2 happens at (X2, Y2, Z2, T2). The timespace interval, S, is found using S2 = (X1-X2)2 + (Y1-Y2)2 + (Z1-Z2)2 – C2(T1-T2)2 = D2 – C2(T1-T2)2, where C is the speed of light and D is the regular (space-only) distance between the events.

What’s tremendously exciting is that not only does the interval stay the same when you change your coordinates through a rotation (regular distance does too), it stays the same when you change your coordinates through motion. This property is why the spacetime interval is so stunningly useful, but it’s also a little tricky to prove. You can prove it using only the fact that the speed of light is always the same (regardless of how you’re moving). What follows isn’t a particularly slick proof, but it works alright.

Things moving at different speeds disagree about where and when things happen. For example, if someone drives by in a car with a blinking turn-signal, they’d say that each of those blinks are happening in the same place (since the driver is moving with the car, and the lights are built into the car, the signal lights are all stationary to the driver), but someone on the side of the road would say that the blinking light is tracing out a dashed line in space (the blinks happen in different places as the car drives by). The driver and the pedestrian are said to be in different “reference frames” and, for example, we could accurately say things like “the distance between the blinks in the driver’s frame is zero”. So, when you’re trying to remember how things can be in different places in different frames or even what frames are, just think: driver/pedestrian.

When considering different coordinate systems we indicate the difference using apostrophes, like this: (X, Y, Z, T) vs. (X’, Y’, Z’, T’). In (almost) everything that follows the Y and Z coordinates will be ignored, since including them just clutters up the math. So events will be written “(X, T)”.

There are three cases to consider:

Light-like, S2 = 0

When two events, (X1, T1) and (X2, T2), are “light-like separated” they’re far enough apart and happen long enough apart that a light beam could travel from one to the other, with no time to spare. Event one could be a photon being emitted, and event two could be that photon hitting something. So, which implies that C|T1-T2| = |X1-X2| which implies that 0 = (X1-X2)2 – C2(T1-T2)2. But, if the speed of light is always exactly the same, then in a different frame of reference

.

Not much to this case. If things are light-like separated, then the interval is always zero, and 0 = 0. Done.

Time-like, S2 < 0

How can a squared number be negative? Don’t worry about it. It’s never necessary to actually solve for S, so S2 serves just fine.

When two events are “time-like separated” they’re close enough together in space, and far enough apart in time, that by traveling at the right speed you can make both events be in the same place. The “blinking turn signal” example is a bunch of time-like separated events, and the driver sees them happening in the same place.

In order to use the fact that light travels at the same speed in all reference frames it’s important to include a light beam in your example. In the “primed coordinates” we make the events happen at the same place at different times, and in the non-primed coordinates the events happen wherever.

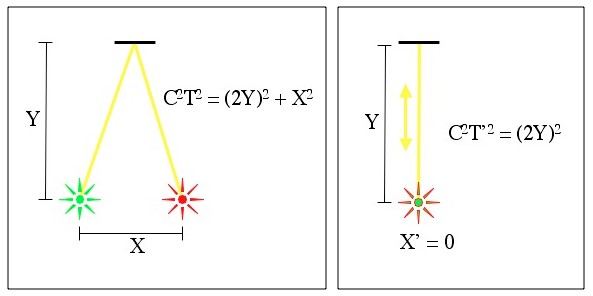

Two events (green and red stars) linked by a beam of light starting at one, bouncing off of a mirror, and arriving at the second.

The total distance traveled by the light beam in the first frame is (by the Pythagorean theorem) , and at light speed the time it takes to cover this distance can be found with

.

In the second frame (with primed coordinates) the total distance traveled is just 2Y, so

What this means is that the interval measured in any frame is the same as the interval measured in the frame where the events happen in the same place (and S2 = -(2Y)2). So, the interval is the same for any frame.

Alternatively, you could make the argument that since Y is unaffected by movement in the X direction, is constant since Y doesn’t change.

Space-like, S2 > 0

Two events are “space-like separated” when they’re far enough apart that light doesn’t have time to travel from one to the other. In time-like separated events there’s a (unique) velocity that you can move at so that both events happen in the same place. In space-like separated events there’s a (unique) velocity that you can move at so that both events happen at the same time (and in different places).

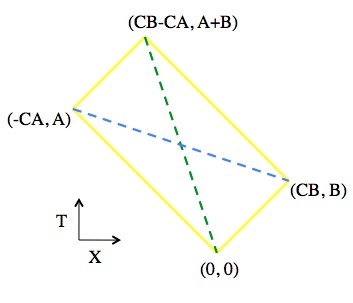

In “spacetime diagrams” the time direction is up and the space direction is left/right (only one space direction, X, is included). The statement that light always travels at the same speed becomes the statement that light rays always trace out 45° angles (or it does with properly chosen units, and otherwise it always traces out the same angle).

A rectangle made of light beams. The bottom point emits two light pulses. After some amount of time (A and B) each is reflected back, and they meet up at the top corner.

A cute property of the rectangle above is that the diagonals are negatives of each other (when measured with the spacetime interval). Here comes a proof!

For the green dashed line, S2 = (CB-CA-0)2 – C2(A+B-0)2 = -4C2AB.

For the blue dashed line, S2 = (CB+CA)2 – C2(B-A)2 = 4C2AB.

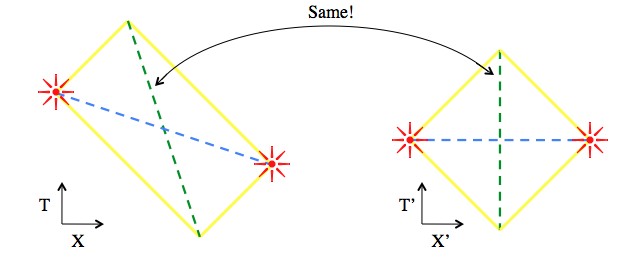

Now, what elevates this fact from “interesting” to “useful” is the knowledge that time-like separated events preserve the interval (last section), and this new fact about the diagonals can be used to show that the interval stays the same for space-like separated events.

The green lines in these pictures are time-like, and the blue lines are space-like. Since the interval between the two events (blue line) is the negative of the green line, and since we already know that the green lines have the same interval, then the blue lines must have the same interval. This means that the interval between two space-like separated events stays the same when you change your frame.

So, the (space-like) interval between two events in a given frame is the negative of the interval between a particular point in the past (which could send a pulse of light to both events) and a particular point in the future (which could receive a pulse of light from both events). Since these points are time-like separated, we already know that changing frame keeps it the same. Changing frame doesn’t change the relationship between the four events in terms of how light travels between them, so we get another rectangle and another set of diagonals. In the new rectangle the time-like diagonals are the same, so the space-like intervals are the same.

Once you’ve got the spacetime interval in your physicist’s toolbox you can almost immediately derive things like time dilation, length contraction, the twin paradox, the list goes on.

Pingback: Q: Since the Earth is spinning and orbiting and whatnot, are we experiencing time wrong because of time dilation? | Ask a Mathematician / Ask a Physicist

Pingback: Q: What is dark energy? | Ask a Mathematician / Ask a Physicist

Pingback: Q: In relativity, length contracts at high speeds. But what’s contracting? Is it distance or space or is there even a difference? | Ask a Mathematician / Ask a Physicist