Physicist: Yes, but…

There are good reasons why casinos make money and “how to gamble” books are longer than two sentences. According to the law of large numbers, if you’re likely to lose a little bit of money in a game, then playing a lot of times effectively guarantees that you’ll lose a lot of money. It doesn’t matter if you think you have “a system”, gambling is a big business and the business is: you lose. But if you do want to gamble there are three simple rules to keep in mind:

1) Don’t.

2) The second you’re ahead, walk away. You’ve already won and it’s all downhill from there.

3) The second you’ve lost money, walk away. It’s gone forever and if you stay it’s just going to get worse.

This system sounds like a clever way to beat any game: just place larger and larger bets, to cover all of your previous loses and a little more, because eventually you’ll win. Then rinse and repeat until Musk and Bezos come begging for a handout.

At first blush this seems like a reasonable trick. And technically it does work. The problem with it is nestled firmly inside that “eventually”. Like so many things in life, this plan works great if you already have an infinite amount of money. With infinite funds, you will win eventually. But without them, you’re screwed as much as always.

Take a simple “double or nothing” scenario like the pass line in craps, where you have a (49.3%) probability of winning. Assuming you bet 1 “chip” (or whatever currency makes sense), then the first round you can either lose or gain 1 new chip. The amount of winnings you can expect (a mathematician would call this “the expected winnings”) is the probability of winning times how much you win, minus the probability you lose times how much you lose:

. This is very intentionally negative, because on average you’re supposed lose.

But if you do lose, then on the second round you can bet 2 chips. That way if you win, you’ll recoup your 1 chip loss and come out 1 chip ahead. If you lose again, you’re down 3, so by doubling your bet again (4 chips), you might recoup your net loses and come out 1 chip ahead. Keep doubling until you win and then you’re back where you started, plus one shiny new chip.

In this scenario you’re guaranteed to gain 1 chip if you keep playing. The question is: how long can you keep playing? What’s missing in the “doubling system” so far is the possibility of losing everything (which is a big red flag for any gambling system). You’re likely to gain a tiny amount (by winning any time before you run out of chips) and unlikely to lose everything (by losing until you run out of chips), but on average you can expect to walk out of the casino with less than you walked in with.

After n rounds you’ve bet chips (you can add this up easily because it’s a geometric series). For example, after three rounds you’ve bet a total of

chips. If you’ve got B chips in your pocket, then after

rounds you’ll be broke.

For example, 1023 chips buys you rounds. For the pass line, the probability of losing ten games in a row and going broke is

and the probability of winning before then and gaining one chip is

. So your expected winnings is

. Despite its cleverness, this system is actually worse than not being clever: if you just bet 1 chip ten times in a row, you can expect to lose about 0.14 chips (and only ten at most).

Long story short, you can change the probability of winning/losing and the amount that you might win/lose by using different strategies or playing different games, but on average you’ll always lose money. By increasing your bet every time you lose, you really can cover your loses and more. Usually. But if you’re one of those unlucky people without infinite funds, then you have to take into account the possibility of going broke. When you do account for every eventuality, you’ll find the casino’s edge is intact.

All that doubling your bets really does is make the chances of winning better while making the consequences of losing worse.

There are a few rare situations where the casino’s edge disappears. A group of MIT kids famously found one in blackjack and exploited it for years. But it wasn’t a big edge, it was very difficult to even know that it was there, and they had to play consistently and with a large bankroll for a long time to overcome the Gambler’s Ruin (which, very succinctly, is: you’ll run out of money before the casino does). But of course gambling isn’t a game, it’s a business. When the casinos figured out what those MIT kids were doing, they just kicked them out.

Casinos are perfectly happy to let you test your theories out. So if you think you’ve got a winning system, it might work. But don’t bet on it.

Gravy: When you want to prove something to death, it helps to do it in extreme generality with everything left as non-specified variables. That way you cover the “yeah, but what if…” questions all at once, which is good, but you often end up in an algebra blizzard, which is work.

Assume that the amount of money you make after placing a bet is described by an gaining factor, f. So if you bet x chips, you either lose x chips or gain fx chips. For example, f=1 is “double or nothing”; if you play x chips and win you get 2x chips back, so you gained 1x chips.

You can sum up the casino’s edge pretty succinctly: fp-q<0. This means that the average amount you lose from betting a chip, q, is more than the average amount you gain, pf. For example, the pass line in craps is f=1, p=0.493, q=0.507, and fp-q=(1)(0.493)-(0.507)=-0.014. Or, if you bet on any particular number in roulette, f=35, p=1/37, q=36/37, and fp-q=(35)(1/37)-(36/37)=-1/37. fp-q<0 is practically a natural law on the casino floor.

Mathematically speaking, the system here is really simple: take whatever your last bet was and multiply it by m (m=2 for doubling, m=3 for tripling, etc.). On the first round you bet one chip, on the nth round you bet chips, and if you win on the nth round, you’ll earn f times your last bet,

.

However, if you lose n rounds in a row, you’ll have bet and lost chips. This means that if you lose the first n-1 rounds and win on the nth, then your take-home winnings are

.

If p is the probability of winning and q is the probability of losing, then the probability of n-1 loses followed by a win is . So P(n) is the probability your ship will come in on the nth round and W(n) is how many chips you gain when it does. With those two equations in hand, you can find your expected winnings, E[W].

That sum blows up when , so if you can keep playing forever, then just by picking a large enough multiplier, m, the expected return is infinite. This is because the number of chips you get back after n rounds increases very exponentially with the number of rounds you play and there’s no chance of ever losing. It’s good to be richer than god.

But in practice, that’s pretty unreasonable. When you walk into the casino, you have a finite number of chips and can play at most B rounds (where B is some distinctly not-infinite number) at which point you run out. In this far more realistic situation, you might win in any of the first B rounds or you might lose every one of them. It’s this “lose every time” scenario that’s ruled out by being infinitely rich. In B rounds you bet a total of chips, which is all of them (because that’s how B is defined). The chance of losing all B rounds is

.

So you’re expected winnings is:

In short, E[W]<0. There are two subtle truths that got weaved in there. First, p+q=1 (the chance of either winning or losing a given round is 1). And second is the casino’s edge, pf<q. This is ultimately where that inequality comes from.

This sort of terrifying algebra storm is why math is so damnably useful: even if you can’t keep an idea in you head all at once, you can still explore it and learn new things from it.

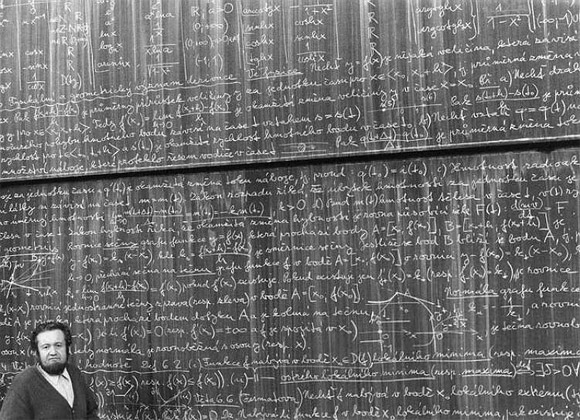

The casino picture is from here.

3 Responses to Q: If you double your bet every time you lose, won’t you eventually win and come out ahead?