Physicist: This has become a whole thing. Although it has shown up in a lot of incarnations throughout history, the most recent is something like this: Computers are getting better all the time and some day artificial reality will be indistinguishable from reality. Also, people love to use computers to simulate stuff, so maybe people in the far future will want to simulate the whole universe. And if they do, they’ll probably do it lots of times. So that means that most of the consciousnesses that will ever exist, will exist inside of those simulations. So all things being equal, you’re probably a simulation. QED

The thing is… there are issues. Right off the bat, you can’t do a full-resolution, real-time simulation of an entire universe inside of a similar universe. Like all simulations, you have to cut corners. Maybe stars outside of our galaxy really are just dots. Maybe atoms are only rendered when someone bothers to break out an electron microscope. As far as anyone will ever be able to tell, there’s no difference between a “universe simulation” and a “perception of the universe simulation”.

Not everything can be swept under the digital rug. You, personally, must exist in some form because you’re thinking about it (right now in fact). More accurately, I must exist. The jury’s still out on you and everyone else. And as long as RAM is a problem, there’s no point fulling rendering everyone else’s mind, so maybe you don’t live in a huge universe simulation, you live in a tiny “you simulation”.

It is not impossible that all of our perceptions, or even our minds, are simulated, but there’s no way to know for sure. And that’s a huge problem. The statement “Hey, maybe we’re all just brains in boxes!” isn’t the beginning of a scientific debate, it’s the unceremonious end of it. The whole point of science is that we can have plenty of theories and ideas, but ultimately the physical universe is what settles debates. Removing physical reality from consideration means that nobody gets to be right or wrong or even informed. Instead of furthering human knowledge, we just get locked into a solipsistic cage match with no referee.

“Our avatars were created in our Simulator’s image and exist by Their whim alone” is… conveniently familiar. But the idea that the super-reality is anything like ours is a hard guess with no solid justification. Without a physical reality to experimentally bounce ideas off of, the scientific process is rudderless. There’s nothing we can usefully say about our hosting super-reality, and even less about the motivations of the “people” living in it. For example, we know that some people do use computers to simulate the universe (nerds), but the overwhelming majority of simulations, especially those with people in them, are used for absurdly unrealistic fantasies (congratulations to Kyle Giersdorf by the way). Therefore, assuming that we’re simulated and all things being equal, our simulation is totally unlike the super-reality where our universe is most likely running on a phone in someone’s pocket. Or it’s being simulated in a dream. Or in a book. Or a spontaneously spawned theocracy of Boltzmann Brains. Or any other mechanism that you’re totally free to make up. How could you be wrong? Double QED!

So declaring the unreality of our reality isn’t wrong, it’s just… not a useful way to spend time when you’re sober. If the simulation is convincing (and it seems to be), then the best you can do is a sort of Pascal’s Computer: given the two possibilities, either the universe is real or it isn’t, you may as well at least pretend it’s real. Keep eating food, don’t walk into traffic, be considerate to animals, etc. You know: live in the world.

That all said, if we do live in a computer simulation that isn’t explicitly designed to fool us, then hopefully there should be some way to determine that fact: scrolling green Matrix code, the same black cat walking by twice, or maybe something more subtle.

Enter James Gates, who noticed something subtle. If you’ve ever heard someone mention that some physicist found evidence that we’re living in a simulation, they’re probably talking about Gates (this has kinda been his thing for a while). The claim has been made that Gate “discovered computer code” in the laws of physics. Before you get too excited about that implying that some physicist found lines of code floating around in Newton’s laws or get overly worried that someone might accidentally execute a “goto 10”, that’s not what he’s talking about and more importantly, that’s not what he did.

Gates is a string theorist who’s unhappy with the equation-centric way physics is done. Which is fair. The universe is described beautifully and (as far as we can tell) perfectly by mathematics, but that doesn’t necessary mean that equations are the best way to do that math. For example, you could talk about light flux by saying “Hey everybody, !” or alternatively you could say “Hey everybody, the total amount of light coming out of any bubble is equal to the amount of light produced in that bubble!”. Gaussian surfaces are a terribly clever way to not do calculus.

Gates found a cute way to talk about the equations of string theory using what he calls “adinkras”, named after the symbols the Akan people used to represent complex ideas. How this is done is a whole thing, and he spell’s out the broad picture in the article he wrote for Physics World way better than I can. Here’s the long and the short of it: when Gates applied his adinkra-nating technique to some of the equations he was looking at, he found that the resulting adinkra had a cute pattern. That in itself is not unusual. Patterns show up all the time.

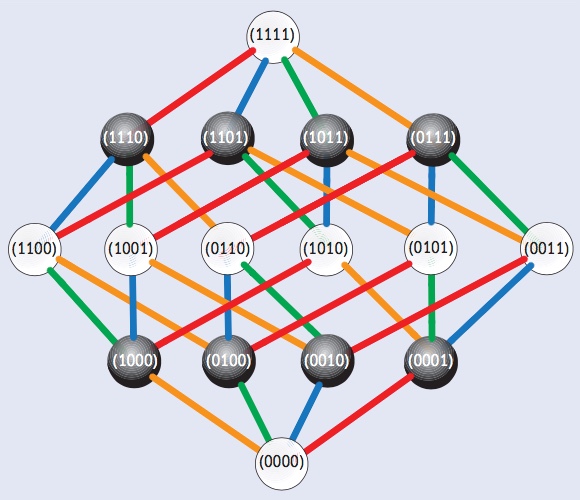

Gates’ adinkra for some string theory equations. Each ball is an equation and the lines are relationships between them (a variety of different derivatives). The numbering is an artificial addition.

This pattern, once some binary digits have been slapped on, looks like a similar pattern that shows up when you deal with “doubly even self-dual linear binary error-correcting block codes“. Not for nothing, it also looks a bit like the skeleton of a hypercube. Patterns show up.

While “doubly even self-dual linear binary error-correcting block codes” does sound very scienceful, it’s also a long way to go to find a matching pattern. Especially considering that the equations in question have nothing to do with error correction. Gates, by way of Wigner, may have said it best:

“… If that sounds crazy to you – well, you could be right. It is certainly possible to overstate mathematical links between different systems: as the physicist Eugene Wigner pointed out in 1960, just because a piece of mathematics is ubiquitous and appears in the description of several distinct systems does not necessarily mean that those systems are related to each other. The number π , after all, occurs in the measurement of circles as well as in the measurement of population distributions. This does not mean that populations are related to circles.”

“Do we live in a computer simulation?” is a great question to ask and a terrible question to answer. Ultimately the simulation hypothesis is a theological idea, not just because it gives us all kinds of new gods to worry about (“Dear usr1, please do not delete me…”), but specifically because it can neither be proven nor refuted by any physical experiment or investigation. Until that changes, we should answer this like other similarly profound questions like: “Is there a really fast, quiet person standing behind me all the time?”, “Does the light stay on when I close the refrigerator door?”, “Did the universe suddenly start, as it is, ten minutes ago?”.

Nope.

16 Responses to Q: Do we actually live in a computer simulation?