Physicist: If you have plenty of chalkboard space and absolutely nothing better to do, you can write down numbers, letters (Greek if you’re δυσάρεστος), and mathematical operators and eventually you’ll have the longest equation ever written down. So if you really want to see the most complicated equation ever, call in sick for a few weeks. A better question might be “what is the most (but not needlessly) complicated equation?”.

There are plenty of equations that are infinitely long, but often they’re simple enough that we can write them compactly. For example, This equation goes on forever, but it’s fairly straight forward: every term you flip the sign and increase the denominator from one odd number to the next. You can write it in mathspeak as

. Like π itself, this sum goes on forever, but it isn’t complicated. You can describe it simply and in such a way that anyone (with sufficient time and chalk) can find as many digits of π as they like. This is the basic idea behind “Kolmogorov Complexity“; the length of the shortest possible set of written instructions that can produce a given result (never mind how long it takes to actually compute it).

If you’re looking for an equation that needs to be complicated, a good place to look is physics (I mean, what else do you really need math for?). If you want to describe the behavior of a ball flying through the air it’s not enough to say “it goes up then down”; there’s a minimum amount of math that goes into accurately calculating the path of falling objects, and it’s more complicated than that.

Arguably, the universe is pretty complicated. But like π, it is deceptively so (we hope). If you want to do something like, say, describe the gravitational interactions of every star in the galaxy, you’d do it by numbering the stars (take your time: star 1, star 2, …, star n), determine the position and mass of each, and

, and then find the force on each star produced by all the others. In practice this is absurd (there are a few hundred billion stars in the Milky Way, but we can’t see most of them because there’s a galaxy in the way), but the equation you would use is pretty straight forward. The force on star k is:

. This is just Newton’s law of gravitation,

, repeated for every possible pair of stars and added up. So while the situation itself is complicated, the equation describing it isn’t. Evidently, if you want an equation that genuinely needs to be complicated, you don’t need a complicated situation, you need complicated dynamics.

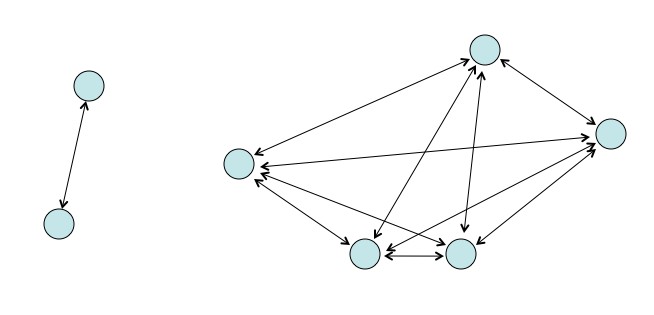

The equation for the gravity between many objects is just the equation for the gravity between every pair added up. Not much more complicated.

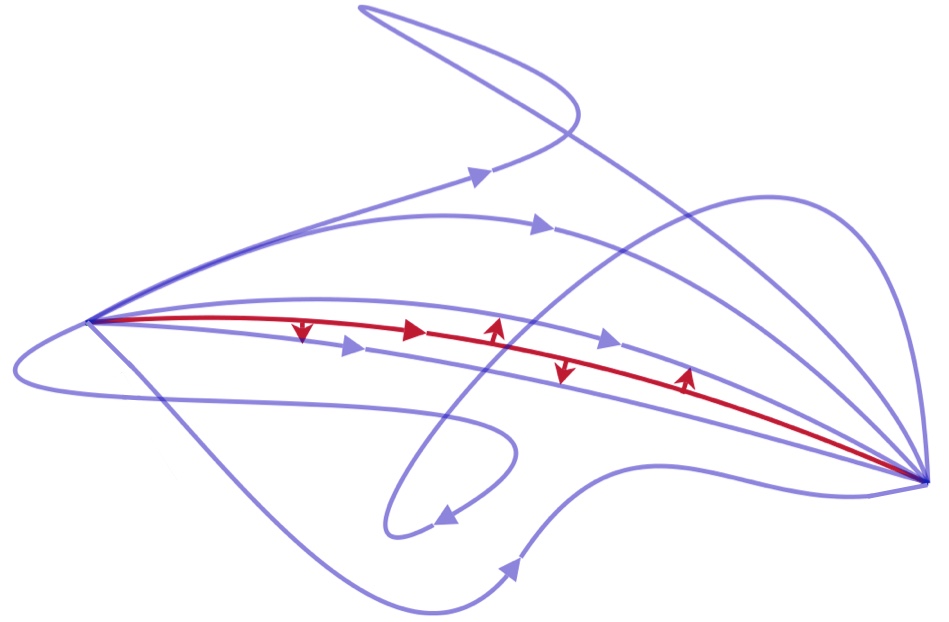

The whole point of physics, aside from understanding things, is to describe the rules of the universe as simply as possible. To that end, physicists love to talk about “Lagrangians”. Once you’ve got the Lagrangian of a system, you can describe the behavior of that system by applying the “principle of least action“, which says that the behavior of a system (the orbit a planet takes, the path of light through materials, etc.) will always be such that the “chosen” path will have the minimum total Lagrangian along that path. It’s a cute recipe for succinctly and simultaneously describing a lot of dynamics that would make Kolmogorov proud.

The Lagrangian gives every point on this picture a value and the total along an entire path is the “action”. The principle of least action says that the path a system will actually take has the least action. With this principle, a single Lagrangian can be used to derive many physical laws at once, so it’s a good candidate for equations that aren’t needlessly complex.

For example, you can sum up Newton’s physics almost instantly. Rather than talking about kinetic energy and momentum and falling, you can just say “Dudes and dudettes, if I may, the Lagrangian for an object flying through the air near the surface of the Earth is , where m is mass, v is velocity, and z is height”. From this single formula, you get the conservation of energy, conservation of momentum (when moving sideways), as well as the acceleration due to gravity. There are also Lagrangians for everything from orbiting planets to electromagnetic fields.

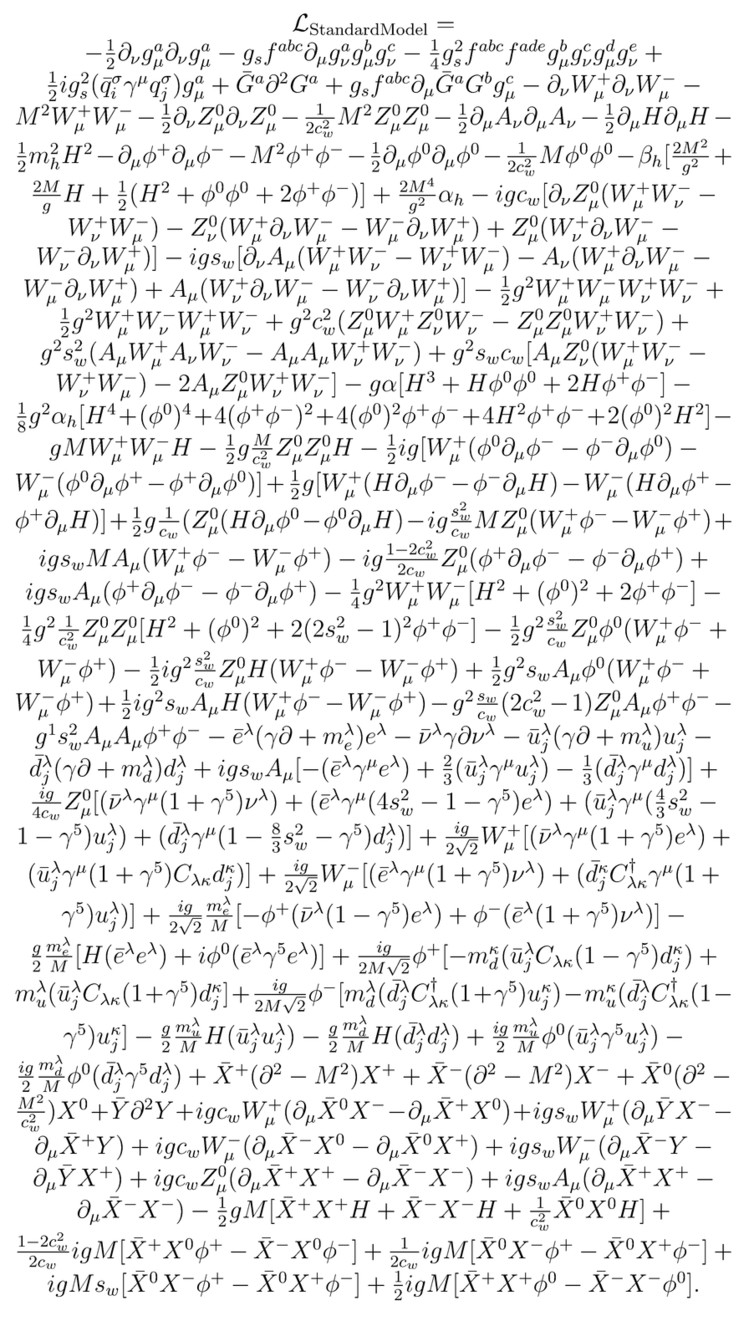

Generally, when you look at the same dynamics applied over and over, the equations involved don’t get much more complicated (although their solutions definitely do). And if you want to describe the dynamics of a system, Lagrangians are an extremely compact way to do it. So what’s the most (but not needlessly) complicated equation in the universe? Arguably, it’s the Standard Model Lagrangian, which covers the dynamics of every kind of particle and all of their interactions. Notably, it doesn’t cover gravity, but be cool. It’s a work in progress.

In some sense this equation is compressed data. All the relevant dynamics are there, but there’s a lot of unpacking to do before that becomes remotely obvious. All equations must have some context before they do anything or even mean anything. That’s why math books are mostly words. “2+2=4” means nothing to an alien until after you tell them what each of those symbols mean and how they’re being used. In the case of the Standard Model Lagrangian, each of these symbols mean a lot, the equation itself is uses cute short hand tricks, and it doesn’t even describe dynamics on its own without tying in the Principle of Least Action. But given all that, it’s describing the most complicated thing we can describe, which is nearly everything, without being needlessly verbose (“mathbose”?) about it.

Answer Gravy: This isn’t part of the question, but if you’ve taken intro physics, you’ve probably seen the equations for kinetic energy, momentum, and acceleration in a uniform gravitational field (like the one you’re experiencing right now). But unless you’re actually a physicist, you’ve probably never been freaked out by seeing a Lagrangian work. This gravy is full of calculus and intro physics.

The “action”, , is a function of the path a system takes,

. More specifically, it’s the integral of the Lagrangian between any two given times:

where t1 and t2 are the start and stop times, is a path,

is the time derivative (velocity) of that path, and

is some given function of

and

. If you want to chose a path that extremizes (either minimizes or maximizes) S, then you can do it by solving the Euler-Lagrange equations:

This is called the Euler-Lagrange equations (plural) because this is actually several equations. Each different variable (x1=x, x2=y, x3=z) tells you something different. In regular ol’ calculus, if you want to find the value of x that extremizes a function f(x), you solve for the value x. Using the Euler-Lagrange equations is philosophically similar: to find the path that extremizes S, you solve

for the path

.

The Lagrangian from earlier, for a free-falling object near the surface of the Earth, is:

For z:

So the E-L equation says:

or

In other words, “everything accelerates downward at the same rate”. Doing the same thing for x or y, you get , which says “things don’t accelerate sideways”. Both good things to know.

You wanna be even slicker, note that this Lagrangian is independent of time. That means that . Therefore, applying the chain rule:

But we have the E-L equations! Plugging those in:

And therefore:

This thing in the parentheses is constant (since it never changes in time). In the case of we find that this constant thing is:

Astute students of physics 1 will recognize the sum of kinetic energy plus gravitational potential. In other words: this is a derivation of the conservation of energy for free-falling objects. A more general treatment can be done using Noether’s Theorem, which says that every symmetry produces a conserved quantity. For example, a time symmetry ( doesn’t change in time) leads to conservation of energy and a space symmetry (

doesn’t change in some direction) leads to conservation of momentum in that direction.

I’ve heard string theoreticians say that the equation describing the string theory, if this theory were to ever become verified, would be the most complicated equation of all physics. But in terms of what we have confirm, this equation is fascinating. The Standard model is fascinating.

The answer is 1.5123742737×10(raised to the power of 10)

Good

Dam.

i solved it its 30549 squared to the square root plus F multiplied by its factorative value. A lot more, but thats broken down.

i got 4

THE LIMIT DOES NOT EXIST

I am in third grade. So one day I asked my sister if she liked math but she said that she liked doing classes about math but hated the actual subject🤔

You can use calculus to solve it

I also got the same answer as anonymous that it’s 30,549 squared square rooted plus F multiplied by it’s factorative value, but the limit does not actually exist.

Answer: 5_X^2(5.6)^8#4/3;920=46

Who else is bored after school and looking up random stuff like me

nice

PARABOLA!!!!

42! (he exclaimed, not factorial).

i learned this stuff in 2nd grade.😅

I got South Africa

im in fourth grade. i thought i was good at math but… and im pretty sure nobody here knows what theyre talking about. There are lots of variables and things in the equations described above, so… the answer would depend on those variables:) most people make up weird equations on these kinds of forums. some of the characters some people put aren’t even valid mathematical functions… hmmmm…

30549 squared to the square root plus F multiplied by its factorative value. OK? 30549 is a pretty big number. Do any of you have a clue about what logic is? I’ll give 2 trillion dollars to anyone who can solve 1/0(without breaking math or creating a nonsensical function). Good luck.

Where can I find the source code of this?

I know this sounds stupid, but why doesn’t that equation involve gravity? Couldn’t you just “mash in” the gravity vectors or whatever?

I’m sorry. I don’t understand math.

hmm most of these things are all nonsense to me…sorry, i’m only in 6th grade so the equations about all that dynamic partical stuff are gobbledegook to me…maybe u could use some complex multi-variable calculus for this?? sorry, but i don’t understand physics

I’m not even gonna try reading that sh*t

lol

wait this is supposed to be complicated?

From the equation of everything, can we get the theory of everything then? Wow! Maths is quite interesting

Purple

It’s dark

Help

i just looked this up cuz i was bored but i SUCK at math i’m so dumb T-T

Guys my answer is correct because I solved it on the calculator the answer is error

nice answer

I’m going to make our math teacher cry 😉

I gotta use matrix for this🤦🏻♀️

ayo this supposed to be hard?

I’ll bet Good Will Hunting could solve that. He was really good at math. (And besides, I’m pretty sure the original guy forgot to carry the 1. Geesh.)

Law of Gravity is not included because Stephen claimed Gravity created the Standard Model.

this is easy get better noob

Pingback: When You’re Afraid to Trust God with Your Future - Curly Girl Life

this sheet is so ez like and rate 5 stars if u agree dawgs

swaglord 69 out!

I LEARNT THIS BEFORE I WENT TO KINDERGARTEN.

I want to be asked more questions about physics

Idk if this is supposed to be easy or difficult

This is crazy how you are able to make an equation of this magnitude to explain something. We haven’t even fully tapped into quantum mechanics and the interactions between the general relativity and quantum theory. These are the things that I think about at night.

ok

I love how there are 15 different answers XD

Huh

Your nose, the I’m in the second grade and I knew this like at first grade

I’ve known the stuff since the preschool grade

@Anonymous. In regards to your comment about solving 1/0 on May 22nd 2020 at 3:48 pm I’d like the money for pointing out the blatantly obvious. 1/0 is not a mathematical formula and couldn’t be solved by the greatest super computer on the planet let alone a human being. However, I applaud your sense of humor, we should have coffee some time and discuss the Riemann hypothesis.

All of you who say you learned this is grades below highschool or collage clearly don’t know the actual answer. I am not saying I know it but still.

Infinity * Everything = Jesus is God